translated by Nguyen Qui Duc, Regina Abrami, Bac Hoai Tran, Phan Thanh Hao, and Dana Sachs

Curbstone Press, 1998

grab a copy here or through your local independent bookstore or library

speculative stories included:

“The Goat Meat Special” (tr. Ho Anh Thai and Wayne Karlin)

“The Man Who Believed in Fairy Tales” (tr. Ho Anh Thai and Wayne Karlin)

“Behind the Red Mist” (tr. Nguyen Qui Duc and Wayne Karlin)

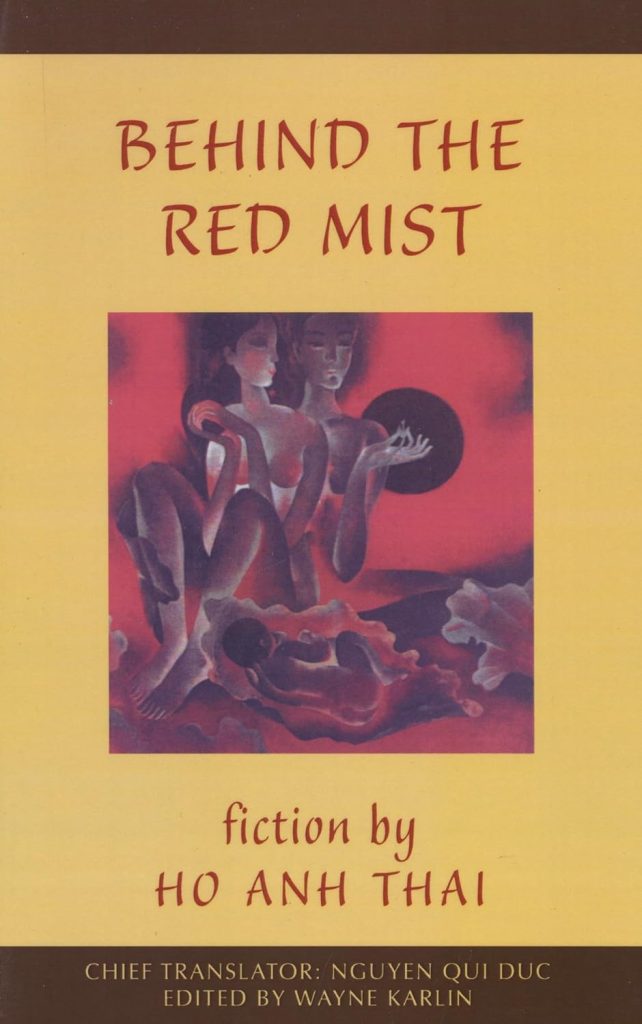

Ho Anh Thai’s Behind the Red Mist is a powerful collection of stories set during and after the Vietnam War, revealing much about the people and culture of that country during the mid-20th c. Of the ten stories included, just a few would be considered “speculative,” but they all offer insight into a world built on family ties, communist bureaucracy, and terror from bombs that could drop from the sky at any moment.

“The Goat Meat Special,” “The Man Who Believed in Fairy Tales,” and the novella “Behind the Red Mist” are surreal stories, verging on magical realism. In “Goat,” a man realizes that his tv displays pornographic movies only when his wife and family aren’t at home. Wondering if it will work if he invites his friend (who’s also his boss) over, Hoi is excited when it does…but then his boss turns into a literal goat. Though goats are often symbols of good fortune and fertility, in Ho An Thai’s story, the goat is a symbol of lasciviousness and promiscuity. The protagonist’s own wife, we’re told at the beginning, once again “slunk off to meet with her boss…Hoi wondered why she was sneaking in and out of the house so much these days” (36). When Dien realizes that he is a goat, he also notices that he can still speak (and even kind of looks like his old self). Hoi hides him, but his wife eventually finds out. She isn’t too surprised (surprisingly), since, as she explains to Hoi, “I saw him for the first time like this on the very day he came to ask me to marry him. My parents and siblings were all full of praise for him: he was so handsome and so talented, a General Manager and barely over 30 years old. Only I saw that coming into our house that day was a sharp bearded goat, insensitive to human beings” (41).

Unexplained transformation is also at the heart of “The Man Who Believed in Fairy Tales,” since the Vietnamese protagonist magically turns into an American after living in the US for a short time. Having gone there just for a six-week training session, he finds one morning that he suddenly has blue eyes and an aquiline nose. This change bodes ill for him, since he is supposed to meet his Vietnamese-American girlfriend’s family. They’re expecting a Vietnamese man, and when they see what he has become, they immediately refuse to let their daughter and granddaughter marry him. Arguments between the generations over marriage partners is a major theme in this collection, revealing deeply ingrained traditions and ideas of honor. When the protagonist returns to Vietnam still looking like an American, people start calling him “Mr. Westerner,” despite the fact that he speaks perfect Vietnamese and tries to explain his situation. Friends and acquaintances then use him and his Western-cultural capital to get what they want, while he’s left depressed and confused. Only at the end of the story, when he pours out his sadness to a neighborhood girl, she consoles him with the following story: “Perhaps one day a fairy would appear who honestly loved me, not because I was a Westerner or for hundreds of other reasons. Only when I met that sincere love would the curse be lifted to me, and I would return to being who I was before” (102).

The past (1960s) and its difficult relation to the present (1980s) is another major theme running throughout these stories. As Wayne Karlin explains in his introduction, Ho Anh Thai’s writing coincides with the period of Doi Moi (“Renovation”), where fiction that otherwise wouldn’t have been allowed by state-owned publishing houses could now be published and distributed:

The policy lifted centralized control and encouraged a market economy in Vietnam; one of its side effects was the permission given to writers to create literature that broke away in form and content from “socialist realism” and that was allowed to criticize the incompetence and corruption of high officials, to depict the losses of war as well as its heroism and sacrifice, to create characters who were complex mixtures of good and bad (cai xau), even if they were communist party members; to write of the personal as well as the social. (xiii)

Many of these features are central to “Behind the Red Mist,” a story about a young man (Tan) thrown back in time after getting electrocuted in 1987. When the high rise apartment building he and his parents and paternal grandmother live in partially collapses, Tan saves his grandmother and runs back to help others, accidentally stepping on a live wire. He wakes up in 1967, in the midst of war. Despite the suffering and destruction all around him, Tan witnesses his parents’ courtship, which is in direct violation of his maternal grandmother’s wishes. Meanwhile, his father is part of a team dredging up a French boat that had sunk during colonial times, with the intention of using it in defense against the American bombers. The boat here functions as a tangible reminder of the past but also as a symbol of transformation and renewal. Experiencing this war-torn past and even hearing about his own birth, Tan more clearly understands how deeply things have shifted in Vietnam since the war ended: the younger generation recoils from violence and any talk of war, wishing to move forward into a market economy, while the older generation is still holding on to traditions and communist ways of life. Tan’s time-travel allows him to act as a bridge, helping his parents find time to be together and potentially softening his maternal grandmother’s opposition.

Behind the Red Mist offers us a wonderfully expressive window onto Vietnam’s past and the ways in which its people have adapted and transformed themselves since the end of the war. Ho Anh Thai’s speculative stories, in particular, display the writer’s versatility in trying to capture the complexities of a country in the midst of change.