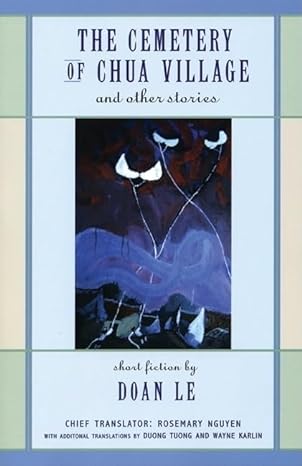

translated by Rosemary Nguyen, Duong Tuong, and Wayne Karlin

Curbstone Press, 2005

grab a copy here or through your local independent bookstore or library

speculative stories included:

“The Cemetery of Chua Village” (tr. Rosemary Nguyen)

“Achieving Flyhood” (tr. Rosemary Nguyen)

“The Venus of Chua Village” (tr. Rosemary Nguyen)

“The Clone” (tr. Duong Tuong with Wayne Karlin)

Doan Le’s The Cemetery of Chua Village and Other Stories includes ten tales, four of which are speculative in some way. Ghosts, metamorphoses, reincarnation, and cloning stand shoulder to shoulder with “realistic” stories of dissolving marriages; greedy land speculators; and tragic, lonely lives. A lovely collection of snapshots offering readers a window onto post-war Vietnam from the perspective of everyday Vietnamese people, Chua Village is an important work of early 21st c. Vietnamese literature.

The collection begins with two speculative stories, setting a slightly surreal tone that infuses the entire book. In “The Cemetery of Chua Village,” a mix-up at a morgue results in a working-class man getting put into a general’s clothes and being placed in an expensive coffin, ready for a state funeral. At once hilarious and sobering, the story is told from the point of view of one of the “ghosts” who already lives in the cemetery. Apparently, when night falls, the skeletons in all their many forms (some still with flesh, some without) open up their coffins and walk around, visiting with friends and family, gossiping, and wondering about who will join them. They know that a new grave is being dug, and when the newcomer arrives, the ghosts knock on the coffin and pepper the ghost with questions until he explains the mix-up and how his son figured out the problem at the very last minute. The narrative voice is folksy and conversational, and the reader is told about life in the cemetery as if it’s nothing out of the ordinary–as if life goes on, just in a different form. As the first sentence of the story notes, “Whether one happens to be alive or dead, it is a very good thing to find oneself surrounded by kindly neighbors” (3).

Magical realism fuels the next story, “Achieving Flyhood,” in which a circus performer trying to get a housing grant from the Ministry turns into a fly when the man reviewing his application says, “You know how it is…too little honey, and too many flies!” (33). As in “The Cemetery,” “Flyhood” strikes a humorous note at the beginning, with the narrator referencing Kafka’s “Metamorphosis,” as if preparing us for what’s to come. What follows is a tale about the former man realizing that being a fly isn’t so bad (despite being prey for a host of predators), especially since he doesn’t need to worry about housing now and the problems that his wife has been giving them since their separation. Indeed, he is found by other humans-turned-flies, who (hilariously) have formed their own complicated bureaucratic structure, complete with titles and in-fighting. The absurdity of the man-fly’s situation highlights the equally absurd human social/political structures that make their workers seem inhuman and applicants feel like they’re in a maze.

“The Venus of Chua Village” is much more subtly speculative, touching lightly on reincarnation and leaving a surreal feeling in the reader’s mind at its end. Here, a painter is approached by a man in the village who needs money to pay off a debt. He offers his sister as a nude model in exchange for payment. The sister, Huong, is not enthusiastic about posing, but knows that they need the money, while the painter finds the whole situation unnerving. Nonetheless, he paints Huong, being careful to include a large red birthmark that appears on her chest. The painting then falls into the hands of a small shopkeeper, who falls in love with a woman whose mother was…Huong. At the end, the story shifts back in time, with the painter asking Huong if she’d like to hear a story about a shopkeeper who has a certain painting….

A speculative story about cloning wraps up the collection, securing our feeling that surrealism and magical realism mark each of these stories, even those that seem most rooted in realistic depictions of life in a Vietnamese village or city. In “The Clone,” a man who ran away from home after his parents divorced and each started new families is confronted by a visitor who looks exactly like his father. Thinking that this must be a step-brother, the narrator is shocked to learn that his visitor is actually a clone of his father. The narrator allows the clone to live in his house for a bit, only to then learn that his mother also cloned herself, and that the two clones have fallen in love. Horrified, the narrator imagines another version of himself being born and going through the grief that he went through for decades. Though he tries to keep the two clones apart, he is ultimately unsuccessful.

Thanks to The Cemetery of Chua Village, Anglophone readers who don’t know much about Vietnam or Vietnamese culture can learn more about the social, political, and cultural aspects of Vietnamese country and city life. Doan Le’s sometimes playful, sometimes deadly serious narrative voices give this collection of stories dimension and endurance in 21st century literature.