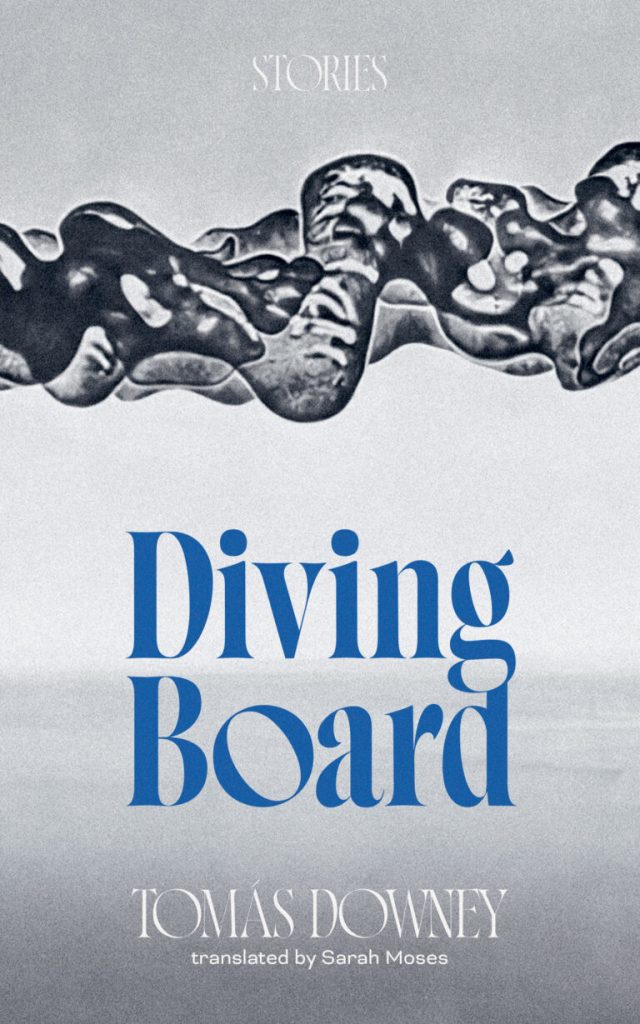

translated from the Spanish by Sarah Moses

first English edition: 2025, Invisible Publishing

192 pages

grab a copy here or through your local independent bookstore or library

Some of the nineteen stories in Tomás Downey’s collection Diving Board are difficult to read–violence happens without warning and is described with a deadpan tone that’s downright disturbing. Other stories leave the reader feeling bewildered, the endings refusing to offer any kind of consolation.

Translated beautifully by Sarah Moses (who also brought us Downey’s story “Bone Animals” in the anthology Through the Night Like a Snake (2024) and Agustina Bazeterrica’s three works in English), Downey’s snapshots are like brief glimpses into a deeply uncertain world. In “The Cloud” and “The Island With No Shore,” the characters seem driven forward without knowing why things are happening to them. The former imagines that a strange cloud has settled over a city, slowly choking the residents. We see everything through a father’s eyes: his wife’s growing insanity, his children’s attempts to help keep things normal. The ending is bleak and offers us no kind of clear ending. “The Island With No Shore” similarly keeps us wondering, like the main character, about why he is making the choices he does. Waking up next to his dead wife, Gabriel simply packs some bags and takes his son to an island where they spend their days fishing and wandering around. We don’t get any explanation for why his wife might have died, but Gabriel doesn’t seem very surprised when he finds her ghost wandering around after a few days. Then again, maybe she isn’t a ghost, since Gabriel’s son sees her and interacts with her. Eventually, she seems more solid than Gabriel himself.

A ghost appears in “Sensitive Skin,” slowly destroying his former girlfriend by hanging around her apartment at random times. When she starts a new relationship, that man, too, starts to decline, but Ines refuses to acknowledge that the ghost might have something to do with it. She simply tries to ignore it, just like the narrator in “Horce,” who buys a seed from a man off the street and plants it just to see what will happen. A full-grown horse emerges after several days, and at first, the narrator just keeps walking by the plant, trying to ignore the hoof, head, and body that is emerging. Once the horse is fully developed, the narrator takes notice and finds comfort in climbing onto its back. Of course, the horse doesn’t last and crumbles into pieces on the floor.

“Astronaut” and “Diving Board” also offer us strange scenarios with no explanations. The former reminds this reader of Thomas Olde Heuvelt’s “The Day the World Turned Upside Down,” since both stories feature people who suddenly find that gravity has betrayed them. In Downey’s story, though, only certain people find themselves stuck to the ceiling, unable to get down without becoming ill. In this, as with most of Downey’s stories, the brevity doesn’t allow us to learn too much about the protagonist’s state of mind, but it does lend an extra dimension of uncertainty and horror to the scenario. The title story, perhaps one of the best of the collection, features a father and daughter on a trip to the pool. Nothing unusual happens at all–in fact, Downey is meticulous in his rendering of banal details, like the color of the little girl’s hairtie or the way the father watches the other kids at the pool to make sure that his daughter is safe and not doing anything dangerous. Absolutely nothing prepares him or us for the fact that, when she finally gets permission to jump off of the diving board, she disappears.

Stories like these are interspersed with those that feature unexpected and disturbing violence. In “Alejo,” the protagonist attacks a classmate without warning, killing her and then drinking her blood, without any explanation for his actions. The adults who surround him and drag him away, and then take him home, seem to stay out of focus and all we read about are Alejo’s once more banal actions and his strange idea that he’ll see Ines again.

The two more science fictional stories of the collection, “The Men Go to War” and “The Takïs,” are Downey-esque takes on time loops and alien invasions. In the former, a woman mourns the loss of her husband in a war that seems to drag on, and every few days, different soldiers come by her house to inform her of his death. They also bring his knife as the only thing of his that they could recover. By the end of the story, the protagonist has many knives in her kitchen drawer and wonders exactly how many. She seems too dispirited to look into exactly why this is happening. In “The Takïs,” brightly-colored fuzzy aliens land on Earth and radiate such a joyful exuberance that almost everyone happily lines up to get on their ships. The narrator’s ex-girlfriend, however, is immune to the aliens and refuses to let him join the others. When the aliens lift off and leave Earth, these two might be the only ones left on the planet.

In story after story, Downey’s characters seem numb, beaten-down, dispirited, or depressed. In this state, they seem unsurprised at even the strangest things, keeping their heads down and trying to ignore that which doesn’t fit into what has become their narrow lives. Only a few characters, like the older lady who’s worked up over a soap opera episode, show any sign of animation. Downey’s ability to tightly control his focus on specific characters and what the reader can see or learn reveals the author’s highly-developed storytelling skills.