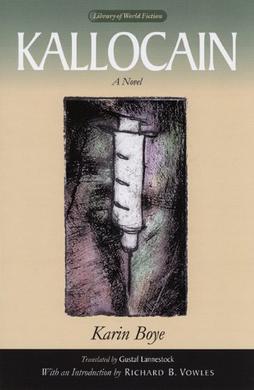

translated by Gustav Lannestock

original publication (in Swedish): 1940

first English edition: 1966, the University of Wisconsin Press

220 pages

grab a copy here or through your local independent bookstore or library

Kallocain is often grouped with Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We (1920, tr. 1924), Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932), and George Orwell’s 1984 (1949) because of its exploration of a dystopian world in which the individual is forced to become part of a faceless collective by a totalitarian government. As Richard Vowles explains in the introduction to my edition, Boye was mostly known as a poet in Sweden, and her experience of World War II likely influenced her writing of Kallocain (and unfortunately, her suicide in 1941). A haunting depiction of one man’s slow realization that he is trapped in an anti-human society, Kallocain offers a more intimate look into the life of a single person grappling with this understanding.

Kallocain is told from one man’s point of view–ironic, since, as the protagonist Leo Kall reminds us throughout his narrative, the individual in this world must give him or herself entirely to the State. Individual desires or achievements are considered treasonous, since each cell only exists to enhance the health and welfare of the larger organism. And yet, Kall is writing this story because, as he explains, though he isn’t quite clear on his purpose, he feels that “this strange connection with my past grew within me, and now I will have no peace until I have written down my memories of a certain eventful time in my life” (4).

Kall, a scientist in Chemistry City No. 4 and the father of three, has synthesized a truth serum that gives its test subjects very few side effects but encourages them to say all that they are feeling (thus helping the State root out subversives). At first, Kall and his boss Edo Rissen experiment on a few subjects that are part of the volunteer service, but the results are so promising that Kall requests permission to expand their testing. Ultimately, he envisions a world in which even one’s thoughts are not one’s own. As she says to his housekeeper, ” ‘From thoughts and feelings, words and actions are born. How could these thoughts and feelings then belong to the individual? Doesn’t the whole fellow-soldier belong to the State?’ ” (13). Indeed, his oldest child, a son, is only allowed to come home a couple of times per week because he’s now being trained as a fellow-soldier of the State. His daughters will follow the same path in a few years.

Despite his success, Kall is disturbed by his boss, who doesn’t seem sufficiently enthusiastic about the Worldstate. Something about Rissen makes Kall question his own thoughts and loyalty, and Kall even wonders if his wife Linda and Rissen had had an affair in the past. As the parade of test subjects moves through his lab, Kall starts to think, against his better judgment, about some of the things these people are saying: one reveals a group that meets in secret to enact strange rituals, while another talks about a wanderer who was murdered but is now seen as a kind of martyr.

Concerns about “meaning” emerge as we move deeper into the book. Kall finds himself surprised at his own growing repulsion when people enthusiastically extol the State. After listening to one particularly energized speech, Kall thinks, “[p]robably never before had I heard it stated so clearly, so to the point, how objectively the value of each fellow-soldier’s contribution must be seen; and yet I felt as if it all was evanescent and trivial. I knew this was a false and unhealthy view, and I tried to convince myself with all possible arguments. But for the desolate emptiness that grew within me I could find no other name than meaninglessness” (124). After forcing his own wife to take the Kallocain, Kall finds out that she, like he himself, has been struggling with a desire to escape from the State’s confines. Later, she explains to Kall that the birth of her children was a major factor in showing her that individualism and families are what give life meaning, not a sublimation of the self into the State: “[c]reation takes place in us. I know that this must not be said, for only the State owns us. But still I’ll say it to you. Otherwise everything is without meaning” (167).

Terrified at his own thoughts, Kall attempts to shift focus onto his boss, whom he suspects harbors these same disturbing ideas. Though Kall reports Rissen to the police, he quickly changes his mind and tries to retract the report but is unable to. His wife, too, has failed to return home one evening, and Kall wonders if it’s because of her subversive tendencies. One evening, Kall is abducted by soldiers from the neighboring state and asked if he will produce Kallocain for them: he agrees. Kall thus writes his narrative from the (very comfortable) confines of his prison in this new state, having never had the opportunity to see his wife or children again. He ends his story by remembering the night he was taken, when, for the first time, he noticed the natural world around him and felt his humanity more thoroughly than ever before.