translated by Margalit Rodgers and Anthony Berris

translated by Margalit Rodgers and Anthony Berris

November 1, 2013

470 pages

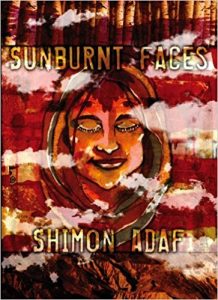

As many reviews of this book will tell you, Sunburnt Faces is not a fantasy so much as it is a novel about fantasy. The concept of “Wonderland,” children’s books about fairies and magical places, and, above all, revelation: these are the foundations of Adaf’s extraordinary, lyrical story. In tracing two important periods in the life of Ori (Flora) Elhayani, Adaf raises questions about the lasting impacts of childhood trauma and loss, the place of fantasy/imagination/spirituality in a child’s world, how friendships and romantic relationships develop and wither, and the cultural and social schisms in Israeli society. Wide-ranging and poetic, Sunburnt Faces invites you to lose yourself in its meditations. It is the opposite of a “tightly-plotted” novel- at times, Adaf seems to wander around in Ori’s childhood (specifically when she’s 12-13 years old), collecting impressions and building her character in preparation for the second part of the book, when we meet Ori again at age 32.

Then again, Sunburnt Faces can also be read as a story about stories; specifically, how they help us narrate our lives and build our identities and memories. Reading, writing, journals, notes, books, bookstores: these occur throughout the novel. Ori reads the children’s series about Ariella the Fairy Detective just as her mother’s health begins to seriously deteriorate and her school friendships undergo significant upheaval. She copies Biblical verses into a private journal, and reads her friend Sigal’s private notes that have been placed in the cracks of a wall (reminiscent of the Western Wall in Jerusalem). As an adult, Ori writes her own children’s books, and spends a lot of time in a bookstore, which was run by an ex-lover about whom she can’t forget, even after marrying someone else.

What makes this novel the most compelling for me, though, is its approach to mystery/the unexplained. The three most important instances of this are: when God speaks to 12-year-old Ori through the TV, when we’re told that Ori suffered an unknown trauma that made her mute for a few months, and when 32-year-old Ori is told that the Ariella books she adored as a girl never actually existed. (Seriously, I want to track down Shimon Adaf in Israel, knock on his door, and demand answers!!) Then again, it’s precisely the lack of answers that makes your brain linger on this novel long after you’ve finished reading it.

Sunburnt Faces‘ nested stories, preoccupation with religious scripture and books that supposedly don’t exist, and literary quotation, combined with its exploration of the liminal space between childhood and adulthood, offer us a fresh, utterly unique take on human nature and human consciousness. I’ll need to read it several more times before I can even begin to understand all of its layers.

I’ll conclude this review with one of the most extraordinary passages I’ve read anywhere in a long time. Here, 12-year-old Ori wakes up in the middle of the night and turns on the TV:

Only the ugly TV, the clock and its figures, remained imprisoned in her gaze. And then God spoke to her from the TV set.

How could she describe His voice?

If every molecule in the living room air was gifted with human consciousness, and each molecule could experience the power of all emotions from the moment of birth to death, and then screamed from the burden of this, or sighed, or bellowed, or lost its voice, or roared with the pain of happiness, or moaned, or groaned with the happiness of pain, or broke into sobs, or shouted for joy, or wept, and the passion of all these sounds was woven into a single syllable, perhaps then it would be possible to begin to describe the richness, the dimensions of the voice.

It came from everywhere in the room. From the minuscule structures of her roaring blood and the DNA helices spiraling in the cell nucleus, from the deposits in the veins and from the fine fatty stalactites trapped in her hair. Her body was a mouth and lips for the voice and the walls also shouted the butter, wonderful sounds, and the cherry-wood sideboard, and from behind its doors, among the bottles as translucent as sapphire, her father’s arrack stormed to give voice to the glory of God, and both the pure and impure uttered the worlds. And yet, the voice that was plucking out her eyes and slicing her skin with ten thousand razors was coming from the TV set.

And God said to her, “Rise, Ori, my light, for your light has come.”

And He let her fall from her life, although she hadn’t realized that she was at such a great height.

And she fell. (11-12)