translated by: see below

translated by: see below

October 27, 2o16

224 pages

If the world needs any book right now, it’s Iraq + 100, edited by acclaimed author Hassan Blasim.

I say that because readers, especially in America and Great Britain, need to hear the stories of the Iraqi people who have lived through over a decade of war and tragedy. Our news reports tell us nothing about the Iraqi psyche, the ways in which art and literature have been shaped by Western invasion, and how Iraqi authors are thinking about the past and the future to make sense of a chaotic present. Us English-language readers are fortunate to have this collection of speculative fiction by Iraqi authors in translation, since we can now catch a glimpse of the vibrant imaginations at work both within that country and abroad.

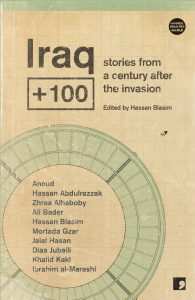

The stories in Iraq + 100 include:

“Kahramana” by Anoud

“The Gardens of Babylon” by Hassan Blasim, translated by Jonathan Wright

“The Corporal” by Ali Bader, translated by Elisabeth Jaquette

“The Worker” by Diaa Jubaili, translated by Andrew Leber

“The Day By Day Mosque” by Mortada Gzar, translated by Katharine Halls

“Baghdad Syndrome” by Zhraa Alhaboby, translated by Emre Bennett

“Operation Daniel” by Khalid Kaki, translated by Adam Talib

“Kuszib” by Hassan Abdulrazzak

“The Here and Now Prison” by Jalal Hassan, translated by Max Weiss

“Najufa” by Ibrahim al-Marashi

In his introduction, Blasim explores the reasons for the lack of a contemporary speculative fiction tradition in Iraq and the historical and political events that have shaped the country’s literature. Unlike the West, whose sf developed alongside scientific development since the mid-19th century, “[k]nowledge, science and philosophy have all but been extinguished in Baghdad, by the long litany of invaders that have descended on Mesopotamia and destroyed its treasures.” With Iraq + 100, Blasim hopes to “imagine the future for this country where writing, law, religion, art and agriculture were born, a country that has also produced some of the greatest real-life tragedies in modern times.” He goes on to call for more diversity in Arabic genre writing and criticizes the “inflexible religious discourse” and “pride in the Arab poetic tradition” for stifling the development of a more complex and diverse Arabic literature. Blasim’s vision is broad and ambitious, and we should all look forward to its realization with excitement.

The stories included in this collection offer us a tantalizing glimpse of that future. From self-aware statues to alien invaders, and from tiger-droids to the ever-present Tigris, these visions of the future incorporate present concerns about health and environmental damage from war, the potential for future dictators and authoritarian states, and questions about how the rich history of the region can be incorporated into Iraq’s future artistic development. Blasim’s story, “The Gardens of Babylon,” takes up this last theme by imagining that Iraq in 2103 is a center for digital technology and innovation. The narrator, tasked with writing “story-games”- turning old tales into new “smart-games”- chafes at the restrictions on his imagination and wishes that he could have been hired to write original stories. And yet, by the end, he acknowledges the pressure of his own past and ancestry on his present artistic vision, just as the story itself, in a meta-fictional twist- offers a version of the writer’s own life.

And then there’s “The Corporal,” in which an Iraqi soldier killed in the American war explains to the reader that he arrived in “heaven” only to be sent back down to Iraq (on the advice of Socrates- yup) a century later. In an attempt to make peace overtures to some American soldiers, Sobhan was shot in the head, but this was the last in a long series of injuries and disfigurements he sustained from life in the army. Here, Bader explores what it was like for Iraqi soldiers to know that the American-led invasion was coming but lack the resources to sufficiently counter it. But in an ironic twist, Sobhan finds that, a century later, it is Iraq that is “saving the American people from dictatorship, and bringing them back their freedom…” Bader turns the language of the Western media and politicians back on itself, thus demonstrating the power of literature to counter propaganda.

Many of these stories imagine a Baghdad/Iraq that has been altered (by Chinese-manufactured domes, alien invasion, etc.) but remains recognizable because of its public spaces and the beloved Tigris. Thus these writers explore the timeless quality of tradition and the weight of history, which reaches into and shapes the future. Zhraa Alhaboby’s “Baghdad Syndrome,” for example, examines how statues of Scheherazade and Shahryar disappear piece by piece but in the process reveal a story of the timelessness of love- specifically, of Baghdad itself.

The stories of repression and violence, including “The Worker” by Diaa Jubaili and “Operation Daniel” by Khalid Kaki, foreground rulers who clamp down on dissent through propaganda and the terror of being turned into pieces of adornment. But the ultimate horror story in this collection is “Kuszib,” told from the perspective of an alien functionary sent to Earth after his race has subjugated humanity and turned humans into literal pieces of meat (for ingestion). Here the language of invasion, subjugation, and self-congratulation point back to the current war and the role of individuals in accepting or rejecting the aggressor’s narrative.

Hopefully we will see more such collections in the future, and more writing from Iraq that pushes the boundaries of speculative fiction.