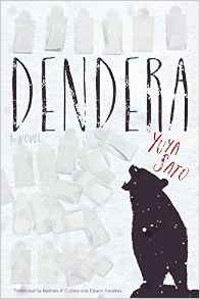

translated by Edwin Hawkes & Nathan A. Collins

Haikasoru

February 17, 2015

400 pages

grab a copy here or from your local independent bookstore or library

Yuya Sato is precisely why you should read speculative fiction in translation. After all, if you were just roaming around a Barnes & Noble, or even many indie bookstores, or looking at the New York Times bestseller’s list, you wouldn’t have come across his latest work, Dendera (orig. publication date- 2009, Japan). And you’d never have experienced the adrenaline-pumping exhilaration and quiet, philosophical discussions of mortality that make Dendera so powerful.

Or as I put it to a friend, “Yuya Sato could write about a box of paper-clips and it would be brilliant.”

The brief author biography at the end of the book notes that Sato is a “writer of ‘strange fiction,’ which features fantastic or horrific concepts treated in a refined literary style.” Yes- “strange” perfectly describes Dendera‘s atmosphere. The novel is difficult to classify. It’s also allegorical in the broadest sense, where no time or place are specified, inviting us to think more about the major questions Sato brings up, rather than historical incidents. I’m usually bored by allegorical tales, but Sato used it in just the right proportion to pique my curiosity.

Dendera opens with one woman “Climbing the Mountain,” a strictly-enforced ceremony for everyone who reaches the age of 70 in the Village. Once you hit 70, you’re taken up the Mountain by a family member and left there to die. It doesn’t matter if you’re a man or a woman, sick or healthy, married or single, brilliant, strong, weak, or violent. This keeps the population level under control and guarantees that in a place where food is often scarce, there will be fewer mouths to feed.

Kayu Saitoh, whose mind we inhabit throughout the novel, has reached the magic age, climbed the Mountain with her son, and waited happily to die. Believing, like many others in the Village, that she’ll go to Paradise where everything is wonderful, Kayu is stunned and enraged to find that, after losing consciousness in the cold mountain air, she was dragged by someone to a different village and warmed up. And she’s still alive.

Thus begins a completely new chapter in Kayu’s life, a kind of life-after-death existence, in a place called Dendera. In reality, Dendera is a small town in Egypt known for an ancient Greco-Roman temple complex, where Aphrodite was worshiped. In the world of the story, Dendera is a community of women who were “abandoned” on the Mountain and left to die, according to custom. It started with a couple of women who refused to submit to what they saw as a brutal and cruel tradition. They reached the other side of the Mountain and survived, somehow, on what they could forage. Eventually, they started rescuing other abandoned women and bringing them to the community. Men, though, were left to die.

You might think that a community of old ladies living by a mountain and starting a new existence would be idyllic, but it really, really isn’t. It’s as harsh and as terrifying as you could imagine. Little food, a rigid social hierarchy, intense cold, and minimal shelter turn these women into shadows of themselves, bringing out their true natures and forcing some, like Kayu, to confront obstacles that they never contemplated back in the Village. With no real tools, weapons, or the ability to make more clothing (except in the rare case when someone kills an animal), the women barely exist. Only one thing keeps a certain contingent going: the determination to wipe out the Village that abandoned them.

Kayu’s entrance disrupts the status quo, since she comes in demanding answers and resisting the women who tell her that she should be glad she was rescued. Throughout Dendera, Kayu and the other women debate the nature of “Paradise,” whether it exists or not, and if being rescued forever bars a woman from entering it when she does die. Ultimately, discussions about the mortality, custom, and the afterlife bring to the surface all of the seething tensions in the community and each woman’s individual goals- destroy the Village, continue to build up Dendera, or wait for death.

Kayu is a particularly interesting character because she not only disrupts the complacency of the community, but does so loudly and vehemently. Kayu may have been unobtrusive in the Village, where her days revolved around caring for children and doing manual labor; in Dendera, however, she is free, and even encouraged, to use her mind to think through problems both philosophical and practical.

Another major point that distinguishes Kayu from the other women is her uncanny instinctual connection to the bear that nearly destroys Dendera. Not long after Kayu arrives in the community, an enormous mother bear begins attacking it, first out of hungry desperation, and later out of pride and anger. And if you’re wondering why I’m ascribing those emotions to a bear, it’s because Sato brilliantly places us in the bear’s mind every once in a while. We learn that the bear’s ultimate goal is to raise a cub to adulthood and then bequeath the Mountain and its environs to that cub. To the bear, the women of Dendera are “Two-Legs” and interlopers. The fact that the women only have spears and no guns gives the bear an added incentive to attack. Each time Kayu encounters the bear, the two look into each other’s eyes, as if sensing some sort of communion. After all, both lived lives of instinct and drudgery, and both must adjust to radically new situations.

Much of the rest of the novel revolves around the many ways in which the women try to trap and kill the bear. The planned massacre of the Village is postponed while they deal with the bear attacks, and each time the creature arrives, it kills one or more women, eating some and merely tossing others aside. At times, the gory details were a bit much for me, but Sato is underscoring the physicality of this story- basic survival is about the material body and what goes into and comes out of it. This physicality is a replacement for the intangible Paradise that Kayu had sought.

Just when the women thought they had driven the bear off for good (or at least for a while), a “plague” starts spreading around the community. Apparently, the same plague had killed several women over a decade before, and this latest outbreak unleashes a continuation of the argument over whether or not to kill the plague-bearers so as to stop its spread. Oh, and then the bear comes back. And Kayu starts wondering if the plague is really that or is actually a calculated attack on the women of the village.

I won’t spoil the ending for you, but I can tell you that it was one of the best endings I’ve read in a long time. Of course, I wanted MORE but that would have diminished the overall power of Sato’s story. So in case you didn’t get this from the rest of the review, I’ll repeat: go read this novel. You will thank me.

(first posted on SF Signal 2/27/15)