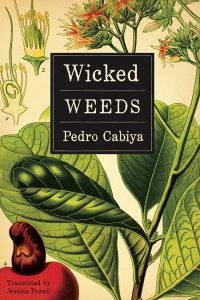

translated from the Spanish (Dominican Republic) by Jessica Powell

translated from the Spanish (Dominican Republic) by Jessica Powell

October 25, 2016

184 pages

Subtitled “A Zombie Novel,” Wicked Weeds is so much more than that. Yes, it is a book whose main character is a self-professed “zombie,” but it is also a work of simultaneously free-wheeling complexity and carefully-plotted exploration of the intersection of the human mind, body, and soul.

But let’s, for the moment, remind ourselves of what the word “zombie” means: “a corpse said to be revived by witchcraft, especially in certain African and Caribbean religions.” As many of us know (and as the zombie and one of his co-workers discuss at some length in the book), the concept of the “zombie” has evolved across time and space, such that in certain films of the last few decades, for example, “zombification” is somehow the result of contagion. Cabiya brings us back to the root (pun intended) of the term, introducing us to an unnamed Caribbean gentleman/scientist/zombie who, unlike the gross, lurching things we see on film, looks and even acts like a real, live human being. He doesn’t sleep, though, so much as lose consciousness from time to time, but he goes to work regularly (he’s the executive vice president of the R&D division of the local branch of Eli Lilly near the border that separates Haiti from the Dominican Republic). Believing that he can find the right compound to give himself some sort of soul, and thus become a human being again, the zombie carries on his project under the watchful eye of three female co-workers, each of whom tries to seduce him on a number of occasions. And on each occasion, the zombie completely misses the point, since he doesn’t feel emotions or sensations.

And yet, Wicked Weeds is not simply the story of this gentlemanly zombie; it is, rather, the scrapbook kept by Isadore Bellamy, one of the co-workers, and also includes scientific observations, fieldnotes, transcripts of interrogations, Isadore’s memories and her great-aunt’s dangerous journey from Haiti to the Dominican Republic (all of which explore the “zombie” figure). The gentleman-zombie’s narrative is written in the first-person, and yet he is not the “author” of this book, just as he sees himself going through his daily routines without really feeling like he’s a living person with goals and desires. He’s like Pinocchio (another story that he refers to at one point)- animated but not alive.

But is he really a zombie? (I won’t spoil this for you- you need to read it yourself). Cabiya makes us think beyond the physicality of reviving a corpse and asks us to think of zombification in multiple dimensions: what does it feel like to try to pass as someone you’re not? What is that specific spark (for lack of a better word) that turns “animated” into “alive”? How is a zombie different from an AI or a wooden doll and why are these differences important? At one point, the narrative (as written by Isadore?) launches into a short treatise on the nature of the brain and its interactions with the body in order to further probe the ways in which the human body functions as one while seeing itself as two (mind and body).

I haven’t even scratched the surface here in expressing the depth, humor, and brilliance of this book. Do yourself a favor and read it.