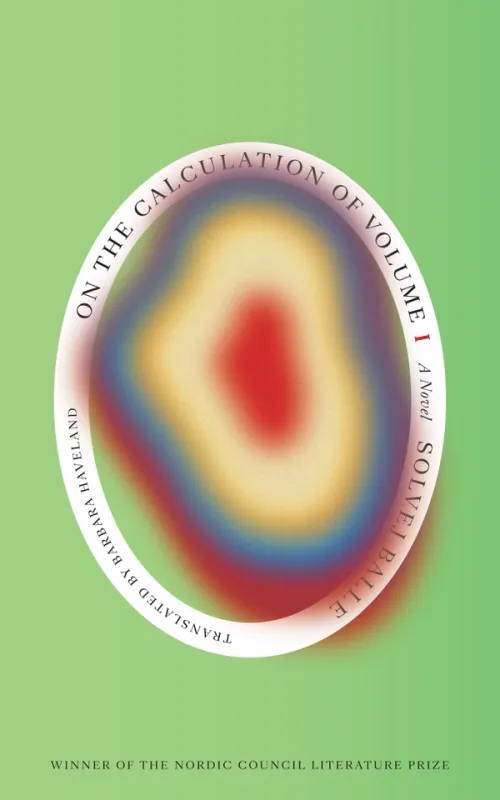

translated by Barbara Haveland

original publication (in Danish): 2020

first English edition: 2024, New Directions

160 pages

grab a copy here or through your local independent bookstore or library

Longlisted for the 2024 National Book Award for Translated Literature, On the Calculation of Volume I is a book in which so much, and so little, happens. As Balle notes in an interview with the editors of Words Without Borders, the idea for a novel about a woman stuck in a single day came to her around the same time the film Groundhog Day was released, though she didn’t see it until later. Her exploration, of course, goes much deeper than the film, the latter only briefly touching on the philosophical implications of being stuck in a single day. Balle, though, plumbs the depths of what might actually happen if a woman found that time moved differently for her than it does for other people.

Tara Selter spends most of the novel, which is made up of her notes about each November 18 that passes, trying to understand what has happened to her. November 18 seemed like a perfectly normal day–she had traveled to Paris to purchase some books that she and her husband had promised clients through their antiquarian book business. Nothing strange happened–Tara attended an auction, bought a few books, visited her husband’s friend Philip, had tea with Philip and his girlfriend in their shop, burned her hand on their stove, and then traveled back home to Clairon-sous-Bois. The next day, Tara notices that things seem to be repeating themselves, and then she sees that the newspapers, tv stations, and calendars all claim that it is November 18. For Tara, it is November 19.

Naturally, she tries to explain what happened to her husband, who is sympathetic but unsure of what to do. Tara spends months trying to think through what happened to her and living the same day over and over. Each morning, she has to explain to her husband why she is back home early and they investigate various theories proposed by physics as to how someone can become trapped in time. Eventually, Tara gives up this lifestyle and moves to the spare bedroom, leaving her husband to go about his November 18 as it was supposed to be, with Tara in Paris and him waiting for her to come home.

Once the full implication of what has happened to her sinks in, Tara tries to understand what it could signify: “[t]hat time stands still. That gravity is suspended. That the logic of the world and the laws of nature break down. That we are forced to acknowledge that our expectations about the constancy of the world are on shaky ground. There are no guarantees and behind all that we ordinarily regard as certain lie improbable exceptions, sudden cracks and inconceivable breaches of the usual laws” (32).

Eventually, Tara moves out of the house completely, taking up residence down the road, making sure to avoid her husband on his daily walk. She realizes that while some things she buys return to their shelves in the store once the “next” day comes, other things remain. Anything she consumes stays where it is, so her books and papers don’t disappear. Anything she eats remains eaten, and she discovers that they then disappear from the store forever. This realization prompts her to go farther afield in her shopping, trying to find the most unusual and unpopular food so that she isn’t taking away from anyone else.

A coin she bought from Philip and Marie returned to its place in Philip’s shop once November 18 repeated itself, and Tara finds it when she travels back to Paris near the anniversary of the incident. Though Tara doesn’t seem to consider it, it might be this coin (and the other two she looks at) that hold a clue to what happened to her. The coin is an ancient Roman sestertius (“two and one-half”), and next to it are “a silver coin bearing the images of Castor and Pollux” and “a copper denar showing the Lighthouse of Alexandria” (143). The sestertius was only issued rarely, but was struck for over 250 years. The Castor and Pollux coin is particularly interesting because, according to Greek and Roman mythology, these were twin brothers, sons of Leda, with one the son of the mortal Tyndareus and the other the son of Zeus. They took care of shipwrecked sailors and sent favorable winds. The Lighthouse of Alexandria was built in ancient Egypt in order to guide ships safely into harbor.

The symbolism of these coins is hard to ignore. Tara feels shipwrecked in time, having run aground on November 18, recognizing that time is functioning differently for her and everyone else. Indeed, as time moves forward for her (the burn she received heals as if she were moving normally through time), she gets the sense every now and then that a different time is moving beneath the one she is experiencing. The 325th November 18th brings her a feeling of October, as if time had been split in two.

Tara returns to Paris for the anniversary of November 18, hoping that everything will return to normal. When it doesn’t, she considers what to do next and how to live in a way that will allow her to move forward without consuming too much. She knows that her husband can’t help her, so she needs to strike out on her own.

Tara’s story is beautifully rendered in English by Barbara Haveland, who, according to that Words Without Borders interview, enjoyed translating Balle’s other novels and was intrigued by the idea of On the Calculation of Volume. As Haveland says, “[t]ranslating Solvej Balle’s work is a rare treat. Her writing is spare and taut. There is nothing superfluous here, nothing random. Every word is weighed, every phrase and sentence finely honed.” One can see this clearly in On the Calculation of Volume I, and, thankfully, we have six more books in the series to enjoy.

Volume II is out in English now. Volumes III and IV will be out in English this November.