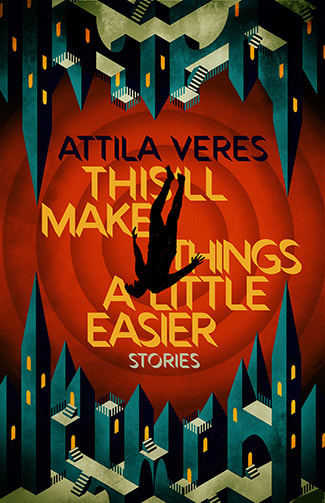

translated from the Hungarian by the author

Valancourt Books, 2026

grab a copy here or through your local independent bookstore or library

Contents:

“‘a pit full of teeth'”

“Transistor”

“The Designated Contact Individual”

“Damage d10+7”

“The Summer I Chose to Die”

“This’ll Make Things a Little Easier” (originally published in English here)

*

I’m not really a horror reader, but when I see that something new is out in English from John Ajvide Lindqvist (Sweden) or Attila Veres (Hungary), I make sure that I get that book into my hands. As in, right away. Veres’s previous collection in English, The Black Maybe: Liminal Tales (also out from the excellent Valancourt Books, translated by Luca Karafiáth) received much-deserved praise for its atmospheric horror and the ways in which Veres patiently and calmly builds up the terror, whether it is in the mode of a Lovecraftian tale or just a little story about a spa vacation that turns into a nightmare.

My spotlight on Hungarian SFT a little over a year ago introduced me to the talented and versatile genre writers that that country has produced, from the Karinthys (father and son) to Péter Zsoldos, Csilla Kleinheincz, Adam Bodor, and Veres himself. Science fiction, fantasy, magical realism, the weird, horror–Hungarian SFT really has it all. Just take a browse of Hungarian Literature Online and search for “speculative fiction” or “horror” to see some of the latest stories and reviews.

But back to Veres. I’m truly impressed that this collection was translated by the author himself. Hungarian is a remarkably difficult language for non-Hungarian speakers to learn, and it is unique in many ways. Thus, moving from Hungarian to English cannot be easy, but Veres makes it sound easy. These stories truly read like they were written by a native English speaker–the cadence, the jokes, the cursing. I had to keep reminding myself that Veres translated this from another language.

This’ll Make Things a Little Easier is a very intentional collection. The first story contains the seeds of two of the following stories, but you wouldn’t realize it unless you were paying close attention to some of the titles, phrases, or descriptions that Veres uses. I nearly zoomed past one reference, just thinking it had been from a different collection or novel that I’d recently read, but I skidded to a stop and did a search of the text. Sure enough, Veres was pointing back to his first story, “‘a pit full of teeth’,” making it retroactively more terrifying.

“‘a pit'” is perfect in its position as the first story of the collection because it is this bizarre combination of hilarious and horrifying. The narrator’s voice is jaded, cynical, offhandedly funny, and also self-aware. The story is, after all, about a writer of horror fiction. In what is likely a horror trope now, the narrator receives a strange email–here, the writer is soliciting a story from him, and it’s all downhill from there. When the narrator sends one of his stories to the supposed anthologist, he learns that the piece will be translated into a foreign language. He then receives money, a copy of the anthology, and a tooth. Of course, the original email address doesn’t work anymore when the narrator tries to write with questions. Worried that his story has been badly translated, he takes the anthology to a professor who specializes in strange languages. And it was here that I thought of another work of Hungarian genre fiction–Ferenc Karinthy’s Metropole, the story of a linguist who finds himself in a country where the language spoken by the residents is unlike anything he’s ever encountered. He can’t decipher it at all. The fact that another Hungarian is writing a story about indecipherability makes me wonder if this is due to the challenging nature of the Hungarian language itself.

But back to Veres and his strange story. The deeper the narrator wades into the translation and the university professor’s reluctance to even touch the anthology, the more dreamlike and twisted the story becomes. Pretty soon, the narrator is hearing the song that is key to his story being played over the radio…except the song shouldn’t exist, since it’s just a title in his story. Then he finds out that that strange language his story was translated into? Yeah, it is actually a vehicle for an obscure people to make reality. The narrator sent them a story and they are sending him a reality that is crafted from his story–the singer who can channel ghosts when she sings, the pit full of teeth…all of it becomes real for him. I’m not even coming close here to representing the skillful craftsmanship of this story–its twists and turns, fascinating revelations, funny asides. It’s the kind of story that makes you say “this should win awards.” Absolutely brilliant.

“Transistor?” Yes, also brilliant. You start to wonder what Veres can’t do and look forward reading much more of his stuff in the future. Honestly, I’ll learn Hungarian myself if his stuff isn’t translated fast enough. But back to the story. “Transistor” is about a family that moves out of their destitute village to a factory where all of the workers are forced to eat this weird sludge three times a day. Their bodies then process this sludge to produce some bluish substance that is then scraped off of and out of them regularly, though no one seems to know what it is ultimately used for. Zsuzsi does, though, for she has been found to have “talent,” and is taken from the factory to be trained in the art of being a transistor–someone who uses The Blue to channel knowledge between many different worlds. Veres focuses not on this fascinating vista of multiverses but on Zsuzsi herself, her life in the grinding factory and then her other life as a transistor, leaving her family behind and feeling guilty, wondering why she is special, learning that her gifts mean that she will not live past forty. Like I said earlier, Veres is patient and crafts his stories with care and deliberation such that you can feel like you’re in the story. Through everything Zsuzsi goes through, she clings to a small shred of hope, even to the end: “She waited for the power of The Blue to fill her; she longed to ascend again–and this time, perhaps, if she rose high enough, she would finally reach the place where she ended and the world began” (86).

Much is made of a fancy watch that one of Zsuzsi’s handlers wears (and that she destroys, just by touching it), but this reader just thought it was an interesting plot device…until it showed up in the next story, “The Designated Contact Individual.” This piece, focusing on a young man desperate to climb the corporate ladder at a soda company, starts off innocently enough. The narrator explains that “Broc Cola is my life” and launches into a theme that marks a few of the stories in this collection–the crushing hopelessness of Hungary itself. As the narrator explains, “I had the feeling that Hungary was closing in on me, pinning me to the ground and preparing to deliver a deathblow unless I tore myself from its grip by force” (87). Feeling rootless, he enthusiastically agrees to move to the next level in the company by becoming a salesman who would travel to “introduc[e] the brand to a new, distant market” (89). Imagine this reader’s surprise when the narrator walks into a nondescript building (looking around for his mode of transportation) where there are some people hanging in the air doing some…transisting? Yes, they send him to a strange land where buildings seem to be thrown together as if just for him, rave parties are attended by huge gods, and what horrifies him the most (wasps) are used to push him to agree to terms with his clients (who eventually become his employers). The price for his success, though, is forgetting…parts of himself, in the form of his memories, start disappearing the longer he stays in this strange place.

“Damage d10+7” is perhaps the most disturbing story of the collection. Balazs, a game master for a real-time narrated role-playing game he has created himself, learns that the fantasy world he built as a way of bringing himself back from a deep depression after a car accident has become real. When one of his clients insists on brutalizing one of his characters, Balazs believes that he can just skip over that incident in his meticulous notes about every game that he keeps. The character, though, seeks revenge, and is able to reach into Balazs’s reality to exact it on him and on the player who attacked her. As in “‘a pit full of teeth’,” Veres has a talent for warping reality to let dream or alternate reality in.

“The Summer I Chose to Die” was strangely similar in theme to another story I had recently read, Korean author Lim Sunwoo’s “You’re Not Glowing” (With the Heart of a Ghost), where an invasion comes not from space but from the oceans. In Veres’s invasion, it’s a race of fish-people, apparently coming up from a sunken, age-old city that channels the Cthulhu mythos. As in Veres’s other stories, though, what comes into focus is not the otherworldly or horrifying but the mundane. Look again at that title: “The Summer I Chose to Die.” The narrator here goes into a lengthy rant (much longer and angrier than that of the corporate climber in “Designated”) about the terrible price that Hungarians have to pay just because they were born into that particular country and its history. Empty, depressed, desperate to do something exciting before dying, the narrator goes on a lengthy drug-induced trip to Croatia with a friend, missing the beginning of the invasion. When they come to, though, they jump right into the war, gleefully killing any fish-people that emerge from the water (at one point, he is glad that Hungary is landlocked). As people start to realize, the flesh of the fish-people, when eaten, produces intense hallucinations. Again, like the corporate climber, the narrator is happy to feel nothing at all after eating this flesh, and after eating the highly-coveted eyes of the fish-people, he goes on a journey that takes him to what sounds like Cthulhu himself…and then he is spat back out. As the narrator grimly assumes, the monster looked into him and saw…itself.

The last story of the collection, “This’ll Make Things a Little Easier,” has no cosmic evil or otherworldly transistor mechanisms. It’s terrifying in its banality. A family struggling financially does what so many other families are doing–they buy a special tree and water it with their blood to make it grow, and then must make pain sacrifices to it in order for it to give them money (the leaves turn to bills in their mouths). The pain must become greater and greater for the money to continue pouring out, but that only drives the inflation up, make people more desperate. The mother in the story is determined to do what she has to do to get more money for her family, no matter what.

This’ll Make Things a Little Easier is a brilliant example of translated horror fiction and its connections across stories add an extra dimension to it that less intentional collections lack. I look forward to more Veres stories in the future, though I’ll be sure to only read them when the sun is shining outside and I’m surrounded by people.