This is part of a series on French author Pierre Boulle.

Julliard, 1971

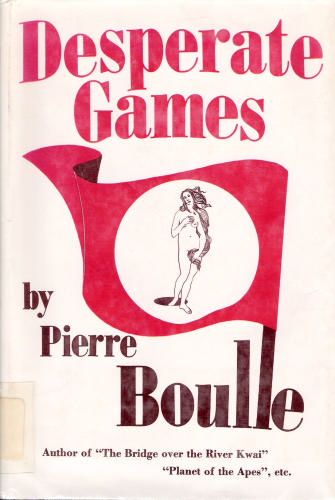

translated by Patricia Wolf

Vanguard Press, 1973

213 pages

If Desperate Games was a person, it would be that kid at school who always kept to himself and seemed perfectly happy with that, who did his own thing without even seeming to notice that others might find that thing strange, and who wore what he wanted without caring about the latest fashions.

Unlike what many of us readers are used to these days, this is not a book about characters and their desires/motivations. This is a book about an idea, one that, as Michael Orthofer says in his review, could spawn several other books. Boulle’s central question is this: what would happen if the foremost scientists in the world formed a global government to solve humanity’s most pressing problems? Well, according to Lucille Frackman Becker, Boulle’s biographer, the author approaches questions like these with the belief that “however admirable [a] scientific goal may be…the methods used to achieve the goal gradually pervert the original intention and lead to an ill-fated denouement” (Pierre Boulle, 80). She cites The Energy of Despair, Mirrors of the Sun, and The Good Leviathan as others of Boulle’s texts that work through this issue.

As I said, characters are not important to Boulle except as vehicles for working out his ideas, which is reminiscent of the Naturalists of the late-19th and early-20th centuries (Zola, Dreiser, Norris, Cather, Crane, Wharton, etc.). The characters of Desperate Games are like chess pieces in a grand game of human nature, history, and scientific progress. I’m certain that if you can get past the woodenness of the characters (and I confess, it was a bit hard for me), then you can really enjoy this absolutely wild, absurd, bizarre, and terrifying novel of hubris and self-destruction.

It all starts off so well. After viewing the nightly news reports with growing disgust over many years, several scientists from various nations (with physicists, biologists, and psychologists prominent among them) decide to form a world government. Their goal: to solve major problems like famine and disease that, they believe, could easily be fixed with some logical, scientific adjustments. To do this, they exchange top-secret information about weapons and battle-readiness and then release a statement to the world’s major newspapers declaring that now the world doesn’t need separate nations or governments and all the leaders should just resign. And they do. Now, that may seem a bit farfetched, but as Boulle’s narrator points out, these leaders have just been looking for an excuse to give up their power. Their people are restless and unhappy, their burdens have become heavier, and they just don’t want to deal with all of the crap that comes with running a country. So they say “great! See you guys later!” and hand over all power to this small group of scientists. Of course, I was waiting this whole time for Boulle to mention the small but vocal group of people that you know would oppose this reorganization of human society. And he does mention it, but briefly. In the world of DG, the vast majority of the world is happy to try something new.

The scientists’ goals are admirable: after fixing the world’s major problems, they turn to raising the intellectual level of all people. To this end, education is totally free and universal…which seems great, until the leaders realize that people are not flocking to school to learn more about the nature of the universe but to gain a deeper understanding of things like…astrology?! Basically, the stupid humans aren’t interested in grand scientific questions but rather in small areas of interest and even pseudoscience. Well that’s disappointing.

To solve this new problem (yes, pretty soon DG reads like a novelization of whack-a-mole), the scientists start sending out the most captivating speakers in their respective fields to jolt their students awake and into caring more about scientific pursuits. Everyone’s still all “meh.” What is a scientist-leader to do?

Oh, and now astronauts and others who operate sophisticated technology have lost their ability to manually control their airplanes, cars, and other vehicles. The onboard computers are so precise that the humans subconsciously give up on trying to make any decisions for the machines. Chaos ensues. Furthermore, the suicide rate around the world has skyrocketed. As in, if nothing is done, the human race will cease to exist. After all, when all of the major problems of the world are solved, technology is streamlined, education is universal, and everything is generally awesome, what’s the point of doing anything?

And let’s not forget that, through all of this craziness, infighting in the government never ceases. Physicists hate the biologists, who loathe the chemists, and all of them hate the literary types, who had to scream and whine until they were allowed to participate in the government at all.

Never one to give up on a problem, Fawell (the leader of the Scientific World Government) turns to the planet’s preeminent psychologist, Betty Han. Always cooler than a cucumber and so logical that one wonders sometimes if she’s actually an android, Han starts coming up with ideas that are so spectacular, they solve the above problems beautifully. Problem is…they’re really destructive. Thanks, cold cold scientific logic.

Enter the eponymous “games.” So Jeopardy or Wheel of Fortune, right? Nope. Think gladiators and lots of blood. Han throws the entire human race back into ancient times when people fought to the death in ampitheaters and audiences cheered them on. Basically, today’s reality tv is tame compared to what Han cooks up. After a while, these “wrestling” championships (which include daggers- how is that wrestling?) get old and the suicide rate, after having plummeted, starts rising again. Han comes up with jousting tournaments, underwater fighting, anything she can think of to rouse the public from its torpor. Nothing works until a mathematician and an astronomer in the government hit on the answer: reenactments of major historical conflicts. And yes, they will be fought with real people, real weapons, real everything. So as not to kill the audiences (thanks, scientists!), these reenactments are filmed and broadcast to theaters around the world with such sophisticated audio/visual technology that Boulle is one step away from VR.

Things get really interesting when the government launches “The Landing,” which replays the Allied invasion of Normandy during World War II. Participants can improve on the weapons of the time but can’t, for instance, use 21st century technology in reenacting that mid-20th century war. One side is led by the physicists, and the other is led by the biologists. Remember that they hate each other? The battle gets very ugly very fast. And then the biologists’ side takes it to a whole new level. And then physicists…well, I won’t give away the ending, because Boulle doesn’t take a breath until the very last page.

Like the narrators of Naturalist novels, Boulle’s maintains a strict distance from the events he describes. Very little commentary comes through, even at the most outrageous points. Rather, he lets the characters condemn themselves, since he believes in the reader’s ability to grasp the terrifying irony of the story. As the bloodshed and insanity escalate, the narrative voice stays calm, taking things to (what Boulle believes is) their logical conclusion.

Desperate Games, then, is an experience. It’s unique, horrifying, and unfortunately, doesn’t seem that far-fetched if you accept some of the not-so-believable premises. Ultimately, it’s a fascinating look at the state of the world just a few decades after World War II and a few years after the threat of nuclear war between the US and the Soviet Union.