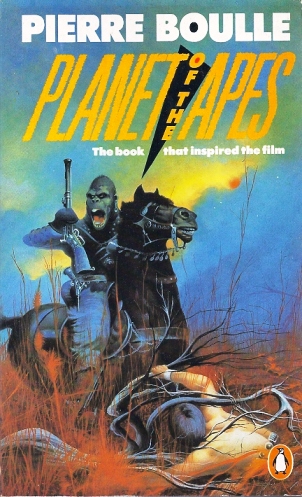

This is part of a series on French author Pierre Boulle.

Julliard, 1963

translated by Xan Fielding

Vanguard Press, 1963

246 pages

If you’ve watched the 1968 Planet of the Apes film, that’s great. Now forget all about it.

Pierre Boulle’s novel Planet of the Apes is, like many of the author’s works, a social satire. Presented in the guise of a literal message in a bottle (but floating in space instead of water), Boulle’s text is narrated by journalist Ulysse Mérou who, along with Professor Antelle, the young physician Arthur Levain, and the chimpanzee Hector, embark on a voyage to the Betelgeuse region, three-hundred light-years away. Embarking in the year 2500 and traveling near the “speed of light minus epsilon,” this crew of discovery reaches the planet they nickname Soror in a few years, while three hundred have passed back on Earth. So far, so good.

Upon landing on Soror, the three men quickly realize that the air is breathable and the food digestible. And then they meet some…strange humans. Without clothing or language, the humans of Soror live in the forests, foraging for food and sleeping in groups. When Ulysse and his companions try to interact with them, the humans act frightened and hostile, at first. As Ulysse notes, these men and women lack a certain “spark” of intelligence and seem content with their very basic lifestyle.

The real shock comes when Ulysse, Antelle, and Levain meet the real rulers of the planet: gorillas, chimpanzees, and orangutans. Dressed in various uniforms and other human clothing, the apes drive cars, live in houses, cook, play sports, and run scientific institutes where humans are the lab rats. Separated from his companions, Ulysse is taken to one of these labs and placed in one of the many cages housing other humans. Desperate to prove his intelligence to the apes studying him, Ulysse learns their language and befriends one of the scientists (Zira). She, in turn, forms a relationship with Ulysse and helps him prove to the scientific leaders that he is not like the other humans, but is from another planet where evolution unfolded differently than on Soror.

During his captivity and over the course of many conversations with Zira, Ulysse learns that the apes of Soror view themselves as the only intelligent species on the planet. Their most important scientific studies center on how they evolved this intelligence while humans did not. Eventually, Ulysse realizes that the technology around him is slightly behind that of the Earth that he left, and another ape scientist confirms that it has been mostly static over the past few hundred years. It’s almost as if apes, which are very good at mimicking humans, were engaged in a very complex mode of imitation…A major archaeological discovery then throws into question ideas about ape evolution and suggests that Soror may have looked a lot like Earth in the distant past.

As a growing number of apes start to worry that Ulysse is inspiring the humans around him to revolt (indeed, he is), a plan materializes to get rid of this bothersome human. Zira and her friends, though, help Ulysse, his female companion (whom he met upon landing on the planet), and their son escape and return to Earth. The homecoming Ulysse receives, though, is not the one he expected…

Boulle uses Planet of the Apes to question humanity’s belief in its own natural superiority. Is human civilization really a given, or is it as fragile as a porcelain figurine? Since we know that apes are able to do many things that humans do, could they, in time, overthrow us and establish their own civilization? Boulle also comments on hierarchies, noting that the chimpanzees, orangutans, and gorillas stopped fighting one another centuries before and focused on pursuing their own talents: the orangutans form the scientific establishment, the gorillas work as hunters and guards, and the chimpanzees are the intelligentsia. In this way, the three groups support one another and rarely tread on one another’s territory.

The apes, Ulysse learns, have the same personality flaws as the humans back on Earth. Orangutans, for example, are the representatives of “official science”:

Pompous, solemn, pedantic, devoid of originality and critical sense, intent on preserving tradition, blind and deaf to all innovation, they form the substratum of every academy. Endowed with a good memory, they learn an enormous amount by heart and from books. Then they themselves write other books, in which they repeat what they have read, thereby earning the respect of their fellow orangutans. (152)

Furthermore, Boulle wonders if on Earth, humans might even be overthrown by intelligent machines, rather than apes:

That perfected machines may one day succeed us is, I remember, an extremely commonplace notion on Earth. It prevails not only among poets and romantics but in all classes of society. Perhaps it is because it is so widespread, that it irritates scientific minds. Perhaps it is also for this very reason that it contains a germ of truth. Only a germ: Machines will always be machines; the most perfected robot, always a robot. But what of living creatures possessing a certain degree of intelligence, like apes? And apes, precisely, are endowed with a keen sense of imitation… (210)

Questions of evolution, civilization, intelligence, and origins punctuate Planet of the Apes and invite present-day readers to continue asking them, lest we let the world we’ve built over the centuries slip between our fingers.