Daniel Haeusser reviews short works of SFT that appear both online and in print. He is an Assistant Professor in the Biology Department at Canisius College, where he teaches microbiology and leads student research projects with bacteria and bacteriophage. He’s also an associate blogger with the American Society for Microbiology’s popular Small Things Considered. Daniel reads broadly in English and French, and his book reviews can be found at Reading1000Lives or Skiffy & Fanty. You can also connect with him on Goodreads or Twitter.

translated by Iain White, Edited by Scott Nicolay

translated by Iain White, Edited by Scott Nicolay

Wakefield Press – September 2021

978-1-939663-70-2– Paperback – 256 pages

Regular followers of SF in Translation may recall my review of the first two comprehensive releases of Jean Ray’s short fiction by the phenomenal Wakefield Press: Whiskey Tales and Cruise of Shadows. These were soon followed by two further volumes in 2020: The Grand Nocturnal and Circles of Dread, which I still have to get and read myself. All translated and annotated by the talented and dedicated Scott Nicolay, the first two volumes that I have had a chance to read introduced me to the atmospheric, haunting prose of this quintessential author of the weird, the so-called Belgian Poe, Jean Ray.

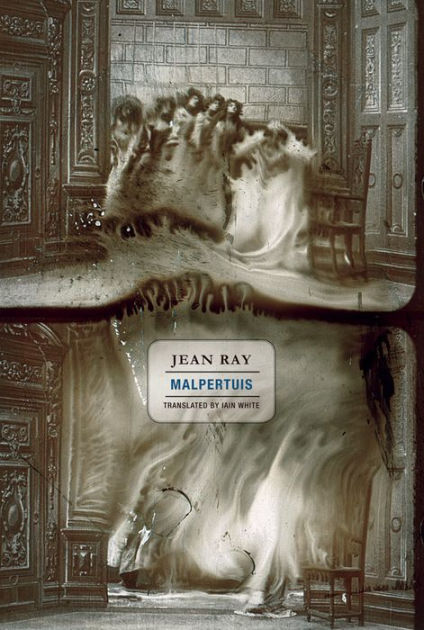

In the introductions for those previous collections, and the notes for some stories within, Nicolay would make praiseful reference to Ray’s chef-d’œuvre, the 1943 novel Malpertuis. These brief descriptions convinced me I’d have to read it. The combination of classic Gothic Horror with the Weird subgenre, in a unique form of the haunted house novel, sounded perfectly tuned to my interests. Even with a foundation of mythological familiarity that was largely lost on me, Malpertuis succeeded wildly in entertaining and impressing.

The narrative core of the novel comes from the diary of Jean-Jacques Grandsire, a naïve young man who recounts his hauntingly bizarre experiences within the dilapidated old mansion called Malpertuis in the secluded streets of Ghent. His recorded story begins in that home at the deathbed of his wealthy Uncle Cassave. Gathering alongside Jean-Jacques to await the demise of Cassave are a motley collection of deviously wary relatives and acquaintances, many among them exceeding the eccentricities of the elder Cassave.

At the opposite end of the personality spectrum to Jean-Jacques is his sister Nancy, a fiery and cunning spirit who won’t abide the antics of the others. There is Philarethe, an obsessive taxidermist who is cousin to Cassave. The Dideloos are uncle and aunt to Jean-Jacques and Nancy. The lascivious eyes of Charles Dideloo linger upon near all, relation or not, excepting his hypochondriac wife Sylvie. With the Dideloos is their foster daughter, Euryale, a young girl with stunning red hair and deep green eyes. Disliked by most are the Cormelon sisters: Eleonore, Rosalie, and Alice, perhaps come to Cassave’s dying side in pure opportunistic momentum. Finally, there is Dr. Sambucque, Cassave’s friend, servant, and physician.

Upon the death of Uncle Cassave, a man named Eisengott arrives to witness the reading of Cassave’s will. The entirety of Cassave’s fortune is left to his collection of relatives, upon the stipulation that they live together within the walls and labyrinthine corridors of Malpertuis for the years to come. However, many those may be. Moving out of the house will result in forfeiture of the fortune. The remaining survivor(s) will be left with the entirety of the inheritance. And if the final two survivors happen to be man and woman, they will need to be married. The normally restrained Euryale flirtatiously whispers to Jean-Jacques a prediction that it shall be them.

With these relatives in the house are others, servants of Malperitus, and formerly of Cassave: domestics Mr. and Mrs. Griboin who have a golem-like hulk of a man who helps them clean, known only as Tchiek. Also haunting the corridors of the house is the mad Lampernisse, the former manager of a paint store that sits adjacent (connected) to Malpertuis. Lampernisse creeps out of the dark corners of the mansion, shrieking of light and colors that vanish from his grasp, and a presence that goes among rooms and corridors snuffing out candles. With Lampernisse’s mind lost, management of the paint shop has fallen to a handsome young man named Mathias Krook.

One can see already there is a complexity to Malpertuis in its cast of characters and their mysterious quirks. The pages of Jean-Jacques’ diary continue in linear narrative from the death of Cassave and reading of the will to a passage of time that increases instances of oddity, clandestine affairs, creeping dread, and outright horror. This culminates with a Christmas dinner where the proverbial shit hits the fan, with an explosion of horror and inexplicable mysteries that seem to break down the walls of reality and perception.

The complexity and riddles only increase, into what blurbs for the novel typically describe as a ‘puzzle box’ of a narrative structure for Ray’s novel. Malpertuis does not begin with Jean-Jacques’ diary. Instead, in a manner familiar to fiction from that era of time (and decades prior) the main story is framed by separate narratives, nested. Even Ray’s short stories often took this form.

For instance, a group of sailors gather in a dockside bar, and one begins to tell a tale about a discovery from the depths of the sea, a captain’s log that has survived the briny waters. The sailor then relates the story those pages contain. This may tell the tale of a man who discovers a book in a monastery that is cursed. And the pages of that cursed tome relate a tale of… And so on and so forth, a recursive nesting doll.

With Malpertuis, Jean Ray does similar, but then also turns the ‘doll’ into a recursive puzzle box, a structure where details are gradually revealed among events that seem to make no rational sense – at first. It’s an exquisitely crafted novel, that readers can then enjoy reading again for fresh discoveries and insights. Ray begins the novel with a story from an unnamed, present-day narrator. One interpretation could be that this character is Ray’s image himself, for roguish similarities abound. This narrator explains that he has just robbed the Convent of the White Penitents. Among the spoils of this crime are manuscripts including Jean-Jacques Grandsire’s diary, the related writings of one Doucedame the Elder, and notes related to these by Father Euchere, Dom of the convent that the unnamed thief has robbed.

Following that introduction, the unnamed thief inserts a first text by Doucedame the Elder, relating exploits on the sea that will hold a familiar sound for any familiar with Jean Ray’s short fiction. Indeed, this part of the novel could exist as a short story unto itself. The story relates a monumental discovery on a Greek Island, and another kind of theft that will only become clear later.

Jean-Jacque’s diary, the bulk of the novel, then finally begins – as discussed above. With this we discover some links with the previous text by Doucedame the Elder. His offspring, Doucedame the Younger, served as a mentor for Jean-Jacques, and that man may still be visiting Malpertuis after Cassave’s death. Additionally, with Doucedame the Elder on the voyage that sets events of the novel into motion is Anselme Grandsire, grandfather of Jean-Jacques and Nancy.

The basic premise of Malpertuis, the purpose behind the voyage, who Cassave is and why he has set up this situation upon his death, the true nature of all these odd characters… These mysteries only become clear as the novel enters into its final pages, after the conclusion of Jean-Jacques’ diary, with further words from Doucedame the Elder and the conclusions reached by Father Euchere when taking it all in. The novel then concludes with a book-ended return to the present-day narrative of the unnamed thief, who travels back to the doors of ancient Malpertuis itself to discover what remains.

Careful and astute readers could possibly figure out the basic premise and mysteries of Malpertuis before all is revealed at its conclusion. One could also just look up information online, or watch the film adaptation of the novel with Orson Welles. But, where’s the fun in that? I admit to looking up details, however, after completing the novel.

Full appreciation of the premise of Malpertuis and its cast of characters demands a good deal of familiarity with Greek mythology. I don’t have that. In fact, I tend to dislike mythology because of its enormous complexity, contradictions, and seemingly endless names, pseudonyms, and personifications. It’s always seemed to me to be a giant entangled mess, the literary or oral tradition equivalent of Immunology. What is wonderful about Malpertuis is that Ray takes that mess of complexity and puts it into a nice well-organized structure, a symbolic haunted house and novel of nested narratives. His perhaps makes the mythology make a bit more sense to me, for all its insanity and weirdness.

Even without the familiarity with Greek myth/characters, I found Malpertuis a fantastically engaging and well-paced read that barely shows its age. It’s a post-modern novel that not only ‘reinvents’ Gothic, haunted house traditions, but also brings elements of quantum realities and multiverses into play in interesting ways, building on cutting edge science around the time of its composition.

[As an aside, the name Malpertuis is also a reference that was new to me. It comes from the name of the labyrinthine castle of sly Reynard the fox, a character from old French (or nearby) tradition. Notes on this by White also revealed to me that renard(e), the French word for fox comes from this character – not the reverse as I assumed. Apparently the oral/literary tradition overtook the original term for ‘fox’ in the French language. See the wonders that literature in translation can reveal?!]

This version of Malpertuis from Wakefield Press uses an existing, respected translation by Iain White, along with his introduction and notes. However, that translation has been updated (edited) here by Scott Nicolay, who translated the short fiction by Ray in the earlier releases. Nicolay also offers a useful afterward here to wrap all up. His translation of Ray’s only other novel, The City of Unspeakable Fear, is forthcoming from Wakefield Press, so Ray fans can rejoice at getting still more.

The pandemic delayed release of Malpertuis. But that and other global calamities (and their after-effects on global supply chains) have also disrupted Wakefield and other small presses. I was pleased to see that after a long unexpected publishing hiatus that they have their first title due for release: The Central Laboratory, verse poetry by Max Jacob, translated by Alexander Dickow. It has both the translation and original French text facing, a concept I applaud. Poetry is not my thing, but if it’s yours, I’d encourage you to check it out, as well as their larger catalog of translation, particularly The School of the Strange, their series of Belgian and French weird fantasy.