translated by Will Vanderhyden

translated by Will Vanderhyden

November 12, 2019

550 pages

Two years ago, I reviewed Fresán’s novel The Invented Part, and even though I somehow managed to convey what I believed the book was about and how it was structured, I’m still, even now, trying to process it.

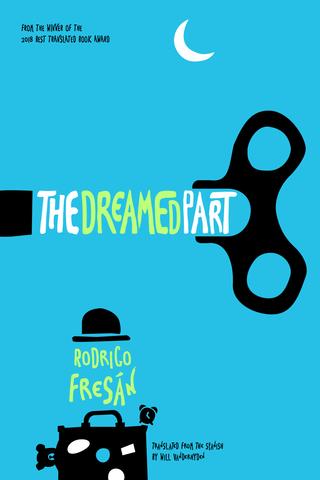

And now Open Letter has given us The Dreamed Part, a sequel that takes up and re-examines some of the same ideas as The Invented Part, but in a different key. In this second novel, Fresán luxuriates in language–its materiality, its mercurial nature, its ability to shape our memories through the act of writing. Here, the narrator of The Invented Part tells us that he has, in fact, failed to merge with the God particle (as he had tried to do in the first novel), and tries to tell us another story: that of a “dream institute” that tried to turn dreams into more efficient vehicles for enabling us to live life to the fullest. This attempt backfired, resulting in people’s inability to even have dreams at all–that is, except for the narrator, who still dreams as much as ever. And always about this one woman with whom he’s in love. And who happens to work at the dream institute.

From there, we move on to the narrator’s sister’s intense obsession with Wuthering Heights, a novel that she (Penelope) has read so many times and internalized so much that it has become a part of her identity. Mixed with this is Penelope’s growing resentment of her attention-and-thrill-seeking parents, who flit in and out of her and her brother’s life and seem to poach everything that their children love, turning those things (Wuthering Heights, a favorite teacher) into playthings. And so, the hazy, mysterious demise/disappearance of the parents in The Invented Part, related to a government crackdown on extremists in the 1970s, comes into focus through this and a later story that the narrator tells. Guilt, resentment, fear: it’s all there.

Did I say “resentment”? Read the narrator’s jaw-dropping, several-page-long rant against the writer he identified in the first book as “IKEA,” and then tell me if that’s the right word. Writing, then, becomes the key to the rest of the novel–how one writes, for whom, where the ideas come from, which ideas should be fodder and which shouldn’t. Vladimir Nabokov gets his own long section here, as the narrator explores his own obsession with Nabokov’s work and the Russian emigre’s use of language as a plaything and a substance with which to experiment.

And finally, the narrator circles back around to what he’d been circling around the entire time–that one particular night when his parents were staging a “happening” at a store on Christmas Eve and pretended like they were guerrilla fighters. And someone (I won’t tell you who!) informed on them, and the mystery of how Penelope and her brother became orphans is solved. That image of the two of them with a man they know as “Uncle Hey Walrus” wandering around the city looking for their parents and knowing that they probably will never see them again is haunting and tragic. And dreamlike.

Until we reach the end of the book where it unfolds what it wants to be: “A book in three movements. Slow motion music. The first movement, that of the dream; the second, that of the waking dream (where you don’t know if it’s headed toward falling asleep or waking up, toward understanding or not understanding what happened); and the third, that of eyes wide open, forcing you to see everything you wanted not to see for so long” (537).

And what the trilogy itself is working toward: “A book with all times at the same time, which, when seen all at once, produce an image of life that is beautiful and surprising and deep. There is no beginning, no middle, no end, no suspense, no moral, no cause, no effect. Nothing but marvelous moments, where invention is the control, dreams the entropy, and memory somewhere in between, somnambulant and ambulating through what is created while awake and what is thought while asleep.”

I’m not sure if any of that made sense. Really, how does one write a review of a novel that is about everything?