originally published in Polish in 1961

first translated into English from the French version (by Jean-Michel Jasiensko, 1966) by Joanna Kilmartin and Steve Cox (1970)

first direct Polish-to-English translation by Bill Johnston (2011)

grab a copy at your local bookstore or here

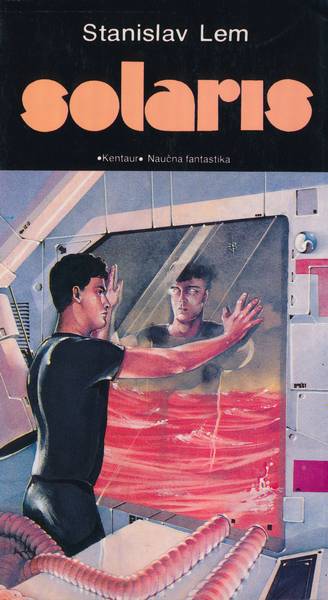

VARIOUS TRANSLATIONS

MY THOUGHTS

*contains spoilers

Much has been written about Solaris over the years, including the differences between the Polish-to-French-to-English translation and the more recent direct Polish-to-English translation. I myself have only read the earlier Kilmartin-Cox translation, but I’d love to compare the two versions at some point in the future.

I recently turned to Solaris, which had been patiently sitting on my bookshelf, after I had read several of Lem’s novels and collections in quick succession (a couple of them twice- specifically, Return From the Stars and Memoirs of a Space Traveler). Immersing myself in Lem’s work, and reading about his life and even his letters to his long-time translator Michael Kandel, has made me feel like I have at least a tenuous understanding of Lem’s major questions and preoccupations: could we ever truly communicate with an alien species? why do humans want to discover new worlds? why do we chase illusions and lie to ourselves about our true motives and desires?

Solaris, like the planet itself, is composed of many complex layers. On the surface, the book is about an astronaut named Kris Kelvin who arrives at Station Solaris and discovers it in disarray. Two of the scientists who have been living on the station and studying the planet have barricaded themselves in their cabins and the third has committed suicide. Soon after he arrives, Kelvin sees his dead lover (who had committed suicide) in his own cabin, and another unfamiliar woman wandering the station, and learns from the two remaining scientists that the existence of these “phantoms” (who look and act and feel like real people) might be due to the planet drawing on the scientists’ subconscious and reconstructing memories in human flesh (though when Kelvin studies a sample from one of these phantoms, he finds that, underneath the usual structures, there is a whole lot of…nothing). Ultimately, Kelvin learns that the three scientists had recently bombarded the ocean with high levels of radiation, which may be why strange things have started happening on the station. The planet’s ocean (which covers most of the surface) is constantly in flux, bringing forth massive outcroppings, mountains, flower-like structures, even entire areas that look like cities. Ultimately, Kelvin and the remaining scientists try to come up with a plan to rid themselves of the phantoms and tell Earth about their experiences before they completely lose their minds.

What interests me the most about this novel is the narrator’s extensive discussion of the decades of research undertaken to understand Solaris. We learn about entire subfields of “Solaristics”- the theories, arguments, encyclopedias, research expeditions, monographs, and institutes that have sprung from the human desire to understand this particular planet and communicate with the ocean, which might be an “intelligent” life form. Pages and pages are dedicated to explaining how biologists, psychologists, chemists, astronomers, and others have moved through various theories and phases of research over the years, producing an entire library of information about the physical characteristics of the planet and speculation about why it acts as it does and what it might mean in terms of the universe generally. Are there other planets like Solaris? What is its purpose? Then again, what is the “purpose” of any planet? Is that even a useful question?

Lem is known for this kind of in-depth chronicling of texts and theories that do not exist: A Perfect Vacuum (1971; tr 1978) includes sardonic reviews of nonexistent books, while Imaginary Magnitude (1973; tr. 1984) includes discussions of the nonexistent fields of “intellectronics” and “phantomatics.” We can also find this quoting and referencing of imaginary books in, for instance, Yoshiki Tanaka’s ten-book series Legends of the Galactic Heroes, in which the narrator often cites passages in history textbooks to bolster his own history (the novels we are reading) of the wars between the Free Planets Alliance and the Galactic Empire. Other books about imaginary books include Calvino’s If on a winter’s night a traveler and Huberath’s Nest of Worlds, and of course there’s Borges’s Library of Babel.

In both Solaris and His Master’s Voice, Lem insists that we acknowledge our inability to ever think outside of our own consciousness. Rather than see this as a kind of surrender, though, we should view it as the first step toward shedding our anthropocentrism and opening our minds to new possibilities (however limited that exercise may be). Lem rejects that kind of science fiction that imagines humans traveling among the stars, meeting and communicating with alien species, and casually turning other planets into versions of our own. What he offers is a type of science fiction that examines our own motivations for exploration and imagines aliens and “messages” from the cosmos that are and will forever remain impenetrable mysteries.

SOLARIANA

Ironically but not surprisingly, this novel that discusses an entire library’s worth of nonexistent research on an imaginary planet has spawned a multitude of articles, essays, reviews, and book chapters that seek to understand it in terms of a variety of disciplines. Listed here is just a sampling of these studies available in English.

” ‘The Genius of the Sea’: Stanislaw Lem’s ‘Solaris’, and the Earth as a Muse” by David Lavery, Extrapolation, 1980-07-01, Vol.21 (2), p.101.

“The Book Is the Alien: On Certain and Uncertain Readings of Lem’s ‘Solaris'” (Le livre est l’extraterrestre: à propos de lectures certaines et incertaines du “Solaris” de Lem) by Istvan Csicsery-Ronay, Jr, Science-fiction studies, 1985-03-01, Vol.12 (1), p.6-21.

“Fluid Worlds: Lem’s ‘Solaris’ and Nabokov’s ‘Ada'” by David Field, Science-fiction studies, 1986-11-01, Vol.13 (3), p.329-344.

” ‘We Are Only Seeking Man’: Gender, Psychoanalysis, and Stanislaw Lem’s ‘Solaris’ (“Nous cherchons seulement l’Homme”: Genre, psychanalyse, et “Solaris” de Stanislaw Lem) by Elyce Rae Helford, Science-fiction studies, 1992-07-01, Vol.19 (2), p.167-177.

“Stanislaw Lem’s Fantastic Ocean: Toward a Semantic Interpretation of ‘Solaris'” by Manfred Geier and Edith Welliver, Science-fiction studies, 1992-07-01, Vol.19 (2), p.192-218.

“The sublime simulacra: Repetition, reversal, and re-covery in Lem’s Solaris” by Neil Easterbrook, Critique, 1995-04-01, Vol.36 (3), p.177.

“Solaris: Stanislaw Lem and the Structure of Cognition” in Critical Theory and Science Fiction by Carl Howard Freedman (2000).

“Mediality and Mourning in Stanislaw Lem’s ‘Solaris’ and ‘His Master’s Voice’ by Anthony Enns, Science-fiction studies, 2002-03-01, Vol.29 (1), p.34-52.

“Solaris! Solaris. Solaris?” in The Art and Science of Stanislaw Lem, ed. Peter Swirski (2006).

“Solaris as Metacommentary: Meta-Science Fiction and Meta-Science-Fiction” by Sandor Klapcsik, Extrapolation, 2008, Vol.49 (1), p.142-158.

“Matter and mutability: Presence and affect in other worlds” by Jane Grant, Technoetic Arts: A Journal of Speculative Research, 2012-12-01, Vol.10 (2-3), p.207-212.

“Stranded contacts: the transformative potential of grief in Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris” in Suicide and Contemporary Science Fiction by Carl Gutiérrez-Jones (2015).

“In space no one can hear you speak: embodied language in Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris and Peter Watts’s Blindsight” by Hubert Kowalewski, Extrapolation, 2015, Vol.56 (3), p.353-376.

“Aliens in Love: Testing Bloom’s Theory of the Anxiety of Influence” by Tõnis Parksepp, Interlitteraria, 2018, Vol.XXIII (2), p.247-262.

“An Analysis of the Foucauldian Elements of Power-Knowledge in Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris and Arthur C. Clarke’s Rendezvous with Rama” (dissertation) by Marie, Junco, 2020.

1 comment on “Review: Solaris by Stanisław Lem”